African Research Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 5(2), 2018

Author: Simon Ndulu

The Catholic University of Eastern Africa,

P.O. Box 62157 – 00200, Nairobi – Kenya

Author E-mail: s.ikonze@gmail.com

Abstract: The purpose of this study was to explore factors that influenced the vulnerability of female domestic workers in Nairobi County. The objectives of the study were to determine how vocational training or the lack of it; awareness of rights among the workers; their socio-economic backgrounds and prior work experience influenced the vulnerability experienced by the female domestic workers. A cross-sectional survey design was applied in the study. The target population was adolescent female domestic workers from ten estates scattered in Nairobi County. A sample size of 47 respondents was picked using purposive and snowballing sampling techniques. Data was collected using a questionnaire. After categorizing the data, simple descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. The study found that domestic work was still viewed by many as difficult, dirty, and demeaning and that domestic workers were paid low wages and worked long hours. The study findings call for implementation of decent work legislation for domestic workers as envisaged in ILO conventions.

Keywords: Domestic work, Female domestic workers, Female domestic workers vulnerability, Female domestic workers wages, Female domestic working hours

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Vulnerability of domestic workers is a global challenge. Domestic work is not specifically addressed in many countries’ legislations (ILO, 2010). As such domestic work lack legal protection. During population census and other surveys, domestic work is categorized under “unorganized labour” (LARC, 2009). Lack of legal recognition left the domestic worker vulnerable to many forms of abuses. Some of the abuses included poor pay (UNICEF, 2004); use of potentially dangerous equipment as well as exposure to hazardous materials (Anti-Slavery, 2009); verbal and sexual abuse (Grossman, 1996); as well as denial of sick and maternity leaves (Margaret, 2009).

Surveys carried out in Kisumu in 2009 and 2010 revealed that domestic workers were paid as little as Kshs.1, 500 per month which was much less than the recommended Kshs.6,000 minimum wage at the time, and that 32% were physically, sexually, or verbally abused in the homes where they worked (LARC, 2010). Similarly, a survey on domestic workers in Mombasa revealed that 92.4% of them lacked a clear contract defining terms of employment (ACILS, 2009). Cases of physical, psychological and sexual abuse have continued to be reported in Nairobi. Media coverage in K-24 by the title “Untold Stories” in the month of January 2011 exposed how women in a group called “Mama Dobi” in Nairobi Eastlands were beaten and forced into sex by their employers. Two weeks later, Kenya Television Network (KTN), in its Prime News on 10th February, 2011 reported a shocking case of a female domestic worker from Mathare Slums who was forced at gun point to bathe a dead body bare-handed.

“Lack of adequate training facilities for domestic workers left hundreds of thousands of men, women and children vulnerable to abuse, neglect, and the cycle of poverty associated with working as domestic workers in Nairobi (Tali-Agler et al., 2006). In a study carried out in Nairobi, Odimu (2005) concluded that the vulnerability of domestic workers demanded serious attention from researchers and policy makers. Further, the Kenya Population and Household Census carried out in 2009 (KNBS, 2009) indicated that 10% of all females seeking work in Nairobi were poised to join a field fraught with vulnerability, even if on transit to a less vulnerable employment. This represented more than one million Kenyans to add to the already more than one million house helps estimated to have been working in Nairobi alone (Wainaina, 2002).

Female unemployment stood at 26% as per the popular report following the national population and housing census of 1999 (CBS, 2002). The report further revealed that a although there have been efforts by the government to improve workers’ situation, women still continue to occupy a disadvantageous position politically, economically and socially. A report attributed to the chief executive officer of the Permanent Public Service Remuneration Review Board (PPSRRB) of Kenya, showed that civil service had 215,331 employees with 156,466 male and 58,865 female and that the bulk of the women were in the lower cadres earning less than KShs. 7,829 per month (Kenya Today, 2011). On the other hand, despite the many and varied efforts put to alleviate the vulnerability of female domestic workers in particular, it is not only enormous but it has refused to go away. Thus, this study sought to examine the factors influencing the vulnerability of the female domestic workers in Nairobi County, Kenya.

2.0 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Study Design

The study adopted a cross-sectional survey design. Gay (1983) defined a survey as an attempt to collect data from members of a population in order to determine the current status of that population with respect to one or more variables. The study’s purpose was to describe the existing issues of female domestic workers. Female domestic workers were asked to explain how they perceived their situation, their attitudes toward their work conditions and behaviours that made them vulnerable while at work. The study explored how variables such as training and awareness influenced the degree of abuse of female domestic workers. Since female domestic workers were spread over a wide area, making direct observation very difficult, interviewing a representative sample was done as it would yield the required information.

2.2 Target Population

The study targeted 90 female adolescents most of whom worked as domestic workers prior to undertaking a vocational training in Nairobi between 2008 and 2009. These females were among vulnerable adolescent girls identified through a Population Council Survey done in Kibera in 2005/2006 (Matheka, 2006) and subsequently sponsored for the training with a view to alleviating their vulnerability. Thus, the population was found suitable for this study because the subjects were believed to possess a considerable experience on vulnerabilities of female domestic work since the time they underwent vocational training. The population was also thought to have acquired the knowledge required to answer the objectives of the study.

2.3 Sample size and Sampling Procedure

Sample size: Gay (1983) suggests that a minimum of thirty (30) cases is required is a descriptive study. Given time and cost limitations and depending on the yield of the snowballing method, the first thirty (30) female domestic workers were to be taken as the sample. Forty seven (47) were contacted whereby ten (10) of them were used for pre-testing the questionnaire and the rest were to be interviewed as respondents. Out of the remaining thirty seven (37), four did not respond, giving a response rate of ninety percent (90%). From those who responded, three were found to be unsuitable due to having not worked as domestic worker either before or after the training. The study findings were eventually based on thirty (30) respondents.

Sampling procedure: Purposive sampling allowed for handpicking of cases because they were informed or possessed the required characteristics. Those identified named others with similar characteristics (Mugenda and Mugenda, 2003). These sampling methods were used in this study because the study focused on acquisition of in-depth information about female domestic workers who had undergone vocational training so as to investigate the degree to which the knowledge acquired had influenced their vulnerability. From alumni list kept by the training institute contacts were made by telephone and those contacted initially were requested to identify others. They did this and even escorted the interviewer to the residences of other respondents. Where a respondent was not available for a face to face interview, telephone interviewing was done after ascertaining by preliminary questions that they had actually attended the training.

2.4 Data Collection Instruments

Structured questionnaire was chosen as a tool of data collection. Clusters of structured questions targeting each variable were prepared. Arrangements for meeting the respondents were done by telephone. The researcher delivered and guided the filling of the questionnaire to the respondents in convenient venues. All the details of the findings were compiled in a row data sheet.

Validity: Mark Saunders et al (2007) defines validity in three ways, namely: As the extent to which data collection methods accurately measure what they are intended to measure; the extent to which research findings are really about what they profess to be about and measurement validity as the extent to which a scale or measuring instrument measures what it is intended to measure. One way validity was used to ensure that the measurement device, in this case the interview guides adequately covered the investigative questions. The contents of the guidelines had been thoroughly discussed with the supervisor and they were further pretested with the alumni. Corrections were then made to make the guides free from ambiguity and more users friendly.

Reliability: Reliability is the extent to which data collection technique(s) would yield consistent findings; similar observations would be made or conclusions reached by other researches or there is transparency in how sense was made from the raw data (Saunders et al., 2007). According to Robson (2002) reliability could be improved by choosing suitable timings, use of structured questions, comparing responses with questions and re-tests. In this study interviews were carried out when the female domestic workers were free and available. Administering the instruments directly by the interviewer to each of the respondents increased reliability.

2.5 Data Analysis Procedure

The collected data were sorted and categorized into the various indicators of the variables under study. Data analysis was carried out by the help of statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Simple descriptive statistics comprising of calculation of averages and percentages were used to present the data.

3.0 RESULTS

3.1 Background Information

The ages of the female domestic workers ranged from 16 to over 28 years. Three (3) or 10% of the study respondents were in the age bracket of 16 to 20 years. Another eighteen (18) or 60% of them were aged between 21 to 24 years, while five (5) or 16.67% of them lied in the age bracket of 25 to 28 years. The remaining four (4) or 13.33% of them were over 28 years old.

Vulnerability of female domestic workers was still rampant with wages averaging Kshs. 4,552.00 per month and working hours being 12.6 per day on average without any compensation. The level of awareness rights in key aspects was also found to be low hence exposing the female domestic workers to exploitation by their employers.

3.2 Vocational Training, Socio-economic Backgrounds and Work Experience

With regard to vocational training, twenty six (26) or 86.67% of the respondents had trained for eight (8) weeks or more while four (4) or 13.33% of them had trained for less than eight (8) weeks. Further, when the respondents were asked to indicate on their socio-economic backgrounds, twenty five (25) or 83.33% of the respondents revealed that they came from a large family with more than 4 siblings. Additionally, twenty (20) or 76.67% of the respondents pointed out that they had poor family background with a total family monthly income of Kshs.6000 or less.

Fourteen (14) or 46.67% of the respondents had received primary level education while sixteen (16), equal to 53.33% of them had secondary education and three (3) or 10% of them had progressed to tertiary colleges. With reference to work experience of the study respondents, one half or 50% of the female domestic workers had two (2) or less years of work experience while the other half had more than two (2) years of work experience.

3.3 Awareness of Rights

The respondents were asked to indicate whether they were aware of the rights of female domestic workers. One (1) or 3.33% of the respondents was aware of training organizations that could assist them to become more empowered. Four (4) or 13.33% of the respondents knew of the existence and functions of KUDHEIHA that could agitate for their rights. Another eleven (11) or 36.67% of the respondents were aware of the Government stipulated minimum wage. On the other hand 70% of the respondents demonstrated knowledge of funding organizations which could help them start businesses in case they wanted to leave domestic work. A vast majority (90%) of the respondents were fully aware of what to do in case of sexual abuse while another 56.67% of the respondents were aware of dispute resolution methods.

3.4 Vulnerability of the Female Domestic Workers

The study also sought to establish the vulnerability of the female domestic workers. An average wage for fourteen (14) or 46.67% of the respondents was Kshs. 4000 or less and the another sixteen (16) or 53.33% of them were paid more than Kshs.4000 Eight (8) or 2.67% had their wages delayed with the majority being paid on time. Sixteen (16) or 53.33% of the respondents worked more than the official eight (8) hours while fourteen (14) or 46.67% of them put in over 12 hours with some working up to seventeen (17) hours per day. Ten or 33.33% of the respondents reported being verbally insulted by their employers. Seven (7) or 23.33% of the respondents pointed out that they were physically assaulted while only 10% of them were sexually abused.

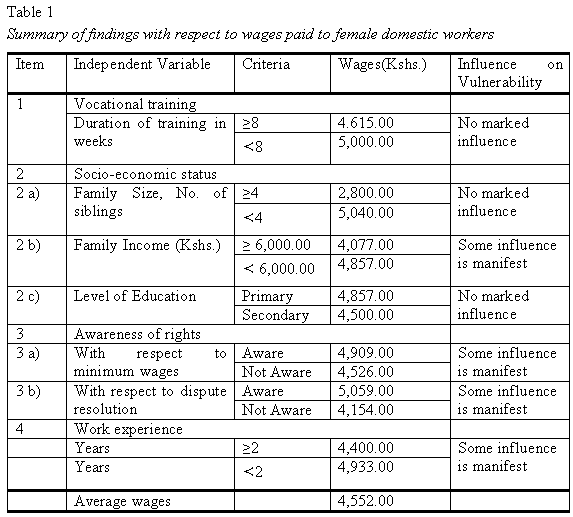

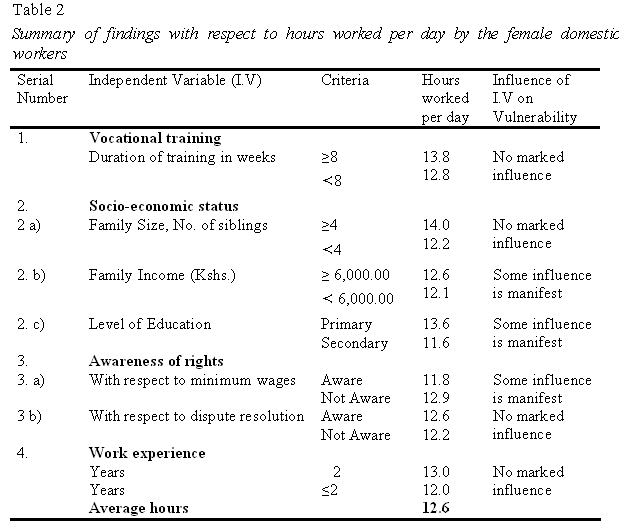

Tables 1 and 2 summarize how two indicators of vulnerability, namely wages and hours of work varied with vocational training, socio-economic status, awareness of rights and prior work experience.

From Table 1 it was clear that awareness of rights influenced the wages paid to the female domestic workers positively. However, this influence was minimal as the wages remained far below the minimum wage of Kshs.7586 and house allowance Kshs.1138, being 15% of minimum wage making a total of Kshs.8724. When it comes to work experience, longer experience also had only a slight influence on the wages as well.

As shown in Table 2 the female domestic workers with better family backgrounds, secondary education and were aware of their rights worked slightly less than the others, although they too were vulnerable to overwork. The average hours of work per day among the respondents was 12.6.

4.0 DISCUSSION

The study found that female domestic workers were vulnerable to their employers irrespective of the length of vocational training which ranged from 4 to 8 weeks, family background, level of education and work experience. The female domestic workers were paid an average of Kshs. 4552 instead of a gross salary of Kshs 8724 as provided for by the International Labour Organization (2011). The respondents worked for an average of 12.6 hours a day, instead of the official eight (8) hours. This meant that they worked for 75.6 hours per week compared to 40 hours stipulated by the Government as per the ILO Convention (ILO, 2011). This showed that the female domestic workers worked nearly twice as long and were paid nearly one half of what was legally expected.

Applying the Geneva 189th convention or standard (ILO, 2011) stipulated-minimum monthly wage and housing allowance of 8724 or Kshs. 54.50 per hour as a base, the female domestic workers should have earned a minimum of Kshs. 16,486. Thus, they were underpaid by Kshs. 11,934 (16,486-4,552). The study therefore showed that there was a gross exploitation of the female domestic workers due to lack of legislation or failure to enforce the same as has been demanded by human rights activists in their campaign known as Haki Haiozi in August 2009 (LARC,2009). Furthermore, the study also showed that there is a need to support the ILO drive to entrench fundamental principles and rights at work as well as tripartism and social dialogue (ILO, 2010).

Vocational training and awareness of rights were found to have some limited significant influence among the female domestic workers as shown in the following sections. The other variables, namely socio-economic status and work experience were found to have limited influence in vulnerability of the female domestic workers.

Vocational training: Another revelation from this study was that NGO-sponsored interventions were not comprehensive and holistic. According to Maria Eitel, president of the NIKE Foundation, a holistic intervention approach included assistance in economic opportunities, health and security, leadership, voice and rights, education, and social mobility which were the key weapons against vulnerability of domestic workers (Maria, 2006). Training girls for a short period, in this case for eight (8) weeks and expecting them to have acquired marketable skills and bargaining powers, did not result in alleviation of their vulnerabilities. According to the Kenya Institute of Education approved syllabus, the minimum period for an effective training should be at least twenty five (25) weeks or six (6) months with an eight (8) week industrial attachment (GOK, 2009).

Awareness of rights: Awareness among female domestic workers with respect to knowledge of the right to a minimum wage was found to be low. A minority of eleven (11) or 36.7% were aware of this fundamental right. A dismal four (4) or 13.3% knew of the existence of KUDHEIHA labour union, and an insignificant 3.3 % were aware of other labour-related organizations such as LARC, IWD (I am Worthy Defending) and KNHRC that could assist them.

To some extent, this explained why their wages were below the minimum wage. It showed that majority of the female domestic workers were still in what Paulo Freire in his “Pedagogy of the oppressed” called magic level of awareness (Paulo Freire, 1968). According to Freire, due to lack of empowering education and poor family backgrounds, those in that magic level learned to accommodate oppressive vulnerabilities as the will of the gods. It is therefore necessary that NGOs that sponsor domestic worker training develop courses that not only emphasize the dignity of labour and honing of skills but those that also exposes the females to strategies that empower them as they struggle to better their lives. Failure to do this will leave female domestic workers still vulnerable and hence continue suffering.

The problems of lack of awareness of unionization and the inability to mobilize critical membership to press for their cause resulted in their vulnerability of bargaining for better pay. This study has revealed this to be the case in the target population and it agrees with the findings of Grossman (1997) and Smith (1996) that “to mobilize a critical membership was a problem and that inability to organize substantial membership meant a weak economic bargaining position”.

5.0 CONCLUSIONS

From the forgoing findings, the following conclusions were reached:

Vocational training offered to the female domestic workers, while imparting a wide range of skills, did not result in better terms of employment in terms of better wages and reduced hours. Its influence on vulnerability was not markedly manifested as it did not alleviate their vulnerability. Further, whether or not the female domestic workers came from a relatively well to do family or had secondary school education or longer work experience did not alleviate their vulnerability of low wages and overwork. Additionally, awareness of rights had the potential to alleviate the vulnerability of the female domestic workers with respect to wages earned and hours worked.

The study recommended that: a specific law should be passed that recognizes domestic labour as a sector of employment and mechanisms be put in place to monitor and enforce compliance with terms of employment. There should be a Kenya Domestic Workers Commission (KDWC). The government should ensure that those NGOs and other interventionists who receive external funding to educate and empower female domestic workers offer verifiable, holistic and empowering training that imparts awareness of rights and improves the domestic workers’ negotiation skills. Further, the government should carry out a survey of all organizations engaged in training women for domestic service with a view to ensuring that such training facilities meet the standard requirements set for domestic workers.

For further research in the area of domestic workers vulnerabilities, there is need to study the effectiveness and relevance of intervention programs and mechanisms by various organizations which are supposed to be empowering domestic workers.

REFERENCES

ACILS /KUDHEIHA (2009). Findings of the domestic workers survey in Mombasa District. Nairobi: Author.

Freire, Paulo(1968). The pedagogy of the Oppressed- Review by Stéphanie Levine and Maryam Nabavi. Toronto: OISE/University of Toronto.

Gay (1983). Introduction to survey sample. Beverly Hills: Sage publications.

GOK/CBS (2002). The popular report of the 1999 ropulation and rousing rensus. Nairobi: Government Printers.

GOK/KNBS (2010). The 2009 population and housing census. Nairobi: Government Printers.

GOK/K.I.E (2009). Homecare Management Level 1, Syllabus and Regulations, K.I.E, Nairobi.

Grace Otieno (2011). Girls challenged on job opportunities,“Kenya Today” January 24-30. Nairobi: Department of Information and Public Communication.

Grossman, J. (1996). My wish is that my kids will try to understand me one day-domestic workers in South Africa (Unpublished Paper University of Cape town).

Grossman J (1997). Summary of submission on Domestic Workers’ to COSATU, South Africa, Quoted -Brenda Grant, Domestic workers. Employees or Servants -Agenda, 61-65.

ILO (2010). Decent work for domestic workers, International Labour Conference, 99th session, 2010 Report IV (I). Geneva: International Labour Office.

ILO (2011). Decent work for domestic workers, International Labour Conference, 100th session. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Kothari, C.R (2004). Research methodology-methods and techniques (2nd Edition). New Delhi, India: New Age International (P) Limited Publishers.

LARC, (2009). HAKI HAIOZI domestic workers campaign. Retrieved from http//www.larc.or.ke/campaign PDF-Downloaded on 24-12-2010 on September 2018.

Levine, S & Nabavi, M. (2004). Review of the pedagogy of the oppressed. Toronto: OISE/University of Toronto.

Margaret, J. (2009). House-Girls gemember: Domestic workers in Vanuatu. The Contemporary Pacific, 21(2), 144-147.

Mugenda & Mugenda (2003). Research methods-quantitative and qualitative approaches. Nairobi, Kenya: ACTS Press.

Nike Foundation (2006). Getting Girls on the anti-poverty agenda, the Synergos Institute. Retrieved from http//www.synergus.org/…/0603nike.htm on September 2018.

Odimu K. N. (2005). Workplace violence among domestic workers in urban households in Kenya. A case of Nairobi City. EASSRR, 23(1), 37-61.

Robson, C. (2002). Real World Research (2nd Edition). Oxford, UK: Black Well Publishing Co.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2007). Research methods for business students (4th Edition). Spain: Mateu Cromo, Artes Graficas.

Smith, G. (1997). “Madam and Even”, a caricature of black women’s’ subjectivity? Agenda, 31,-Quoted in Brenda Grant, Domestic workers: Employees or Servants

Tali, A., Maura, K., & Jillian, T. (2006). Culture clash: Domestic workers and their employers in Kenya, (Unpublished Research, University of Nairobi).

UNICEF (2004). Efforts against child labour often overlook domestic workers. Geneva, NY: Sages Press.

UNICEF (2010). Slum women struggle to put food on the table Nairobi. Retrieved from http//www.osfea.com/1.html on September 2018.

Wainaina M. (2002). Training and empowerment programs for female domestic laborers in Nairobi, Kenya: Implications for alleviation of female poverty, (Unpublished thesis, University of Nairobi).